the ralph bateman collection

A WHITE GLOVE auction WHERE EVERY LOT WAS SUCCESSFULLY SOLD

Wednesday 15 November 2023

HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE COLLECTION

ralph bateman

1 September 1925 - 11 August 2011

Ralph Bateman was called an eccentric, a loner, even a shark in his lifetime. He certainly never followed the herd although he sought security and freedom from obligation to others rather than wealth. He was also called generous, self-effacing and a family man. He seemed to have little need for friends and even less for acquaintances although his family and his few friends loved him dearly. Having achieved financial security, he taught himself about the Arts and collecting jewellery, furniture and paintings became his passion.

Ralph was born in Sydney Australia in 1925, the fourth of five children. He felt an outsider at home and that marked a pattern in his life. His parents were Plymouth Brethren, a strict Christian sect founded in Plymouth, England in the nineteenth century which later established many communities in Australia. Brethren practices were probably not as severe in 1925 as they later became but church was at the centre of life and members tended to socialise together and work in Brethren businesses. Leaving the sect could result in an ex-member losing their job and being shunned by family and friends. Ralph and his two brothers may not have broken formally from the Brethren but they rejected Christianity when they grew up, indeed Ralph refused to allow his children to attend Sunday School on the grounds that they needed to be protected from the propaganda of organised religion. On the other hand, religious music was one of his great loves and in his retirement, he would slip into St Pauls Cathedral to hear the sung Evensong whenever he was in Central London. Neither Ralph nor his siblings spoke much of their upbringing which suggests that there may have been few happy memories but times were hard for everyone in the 1930’s and they were fed and clothed.

The youngest boy Alan, who arrived when Ralph was two, was the favourite child and both Ralph and his next sister Gwen felt unappreciated. Their relationship with their mother “Ma” was fractious. Ma worked throughout their childhoods, first in a corner store attached to their home and later as a secretary to an undertaker. She was a stern woman with little humour. Their father “Pa” by contrast was kind and loving. He made the metal “slugs” which printers used to create their printing plates and designed and built for himself a machine to make the slugs. Pa’s three boys enjoyed running round the city delivering packets of slugs to customers.

All three sons enlisted to fight in World War Two. Ralph had training in the air force in Australia and Canada but the war finished before his unit was ready to fight. Likewise Alan had training but was too young for action. Their oldest brother Howard did see action but was taken prisoner and died in a prisoner of war camp in 1943.

After the war, returning soldiers were offered a free place at university by the Australian government which transformed the lives of Ralph and Alan who could never otherwise have been able to study beyond school. Ralph became a dental surgeon and Alan a distinguished entomologist. In 1951, not long after qualifying, Ralph set sail for the UK. In those days in Australia it could take years for a dentist to earn enough to buy into a dental partnership but a trip of a few years to the UK enabled young dentists to save enough by working in the new National Health Service.

Ralph’s mother accompanied him to the UK. She was not close to Ralph but she and her husband may have had difficulties in their marriage. Divorce was not an option in the Plymouth Brethren, so escape to Europe may have been the only way to resolve their differences.

He bought a small dental practice with a flat attached in Roman Road in the east end of London and set his mother up in the flat where she remained for the rest of her life. He soon bought a second much bigger dental practice nearby in Mile End where he employed six or more dentists and started to earn real money. Many years later he bought another large practice in Pimlico.

His work took him to the London Hospital in nearby Whitechapel and in the Xray department he met Betty Brooks, a young receptionist. They were soon married and had two daughters. It was the turning point in Raph’s life. He adored Betty and never tired of recounting her virtues to anyone who would listen. She in turn devoted herself to him.

In the early 1960s, Ralph branched out from dentistry almost by accident. He found he couldn’t sell his home because several of his neighbours wanted to move at the same time. Frustrated by the delay, Ralph conceived of buying a couple of his neighbours’ homes so that potential purchasers would not be discouraged by the row of “for sale” signs. It didn’t take long for a sharp young estate agent to suggest to him that he could make money if he purchased and demolished all six unremarkable and unsaleable detached houses with sizeable gardens and replaced them with fifty new, smaller homes each with three bedrooms.

Many years later, Betty confessed that it was terrifying to borrow so much money (from family and friends as well as from the bank) and that it took a couple of years to make a return, but the gamble paid off. The risk and eventual reward was exhilarating to Ralph and he undertook several more property projects which made him a wealthy man.

As Ralph starting to make his way as a dental surgeon a director at Cottrell & Co in Charlotte Street, London, where he obtained his dental supplies, spotted his potential and decided to mentor him. Ralph used to relate with tears in his eyes how the man taught him to order from a restaurant menu, use cutlery politely, pay a tip, make small talk: which helped him feel a little less foreign in 1960’s Britain. He also introduced Ralph to art galleries and to classical ballet which would become his passions.

Ralph was a practical man. He taught himself plumbing so that he could install central heating in his own home and in the homes he financed. It proved an excellent way for him to keep an eye on his builders: not the skilled trades (bricklayers, carpenters, roofers, scaffolders and the like) whom he much respected, but the managers whom he feared might try to rob him of materials or delay the build or run the project badly. He wore conventional work clothes on site but the Tupperware box of homemade fruit salad and copy of the Financial Times which he always carried may have aroused suspicions.

Likewise, he did not reserve the best dentistry work for himself as proprietor. He observed that many young dentists disliked pulling teeth and making dentures, both because they were less profitable than fillings and because they were the hardest skills to master. He volunteered to take on all the extraction and denture patients, which pleased both dentists and patients. Indeed a Council notice in the local Post Office in Pimlico recommended him as the only dental surgeon in the neighbourhood who would make NHS dentures.

He was reluctant to spend money if he perceived it inessential or a luxury. On holiday in Paris, he learned that dishes cost less in a diner if they were eaten standing at the counter rather than sitting at a table and thenceforward the family ate nearly all their Parisian meals at the counter: fine for the parents but his young children had to get used to stretching up and picking their food from unseen plates high above them. After retirement, he would never leave home without his free transport pass and once when Betty forgot hers, he insisted that they go home for it, even risking being late for the ballet where he had paid £150 a ticket. Betty learned to play the game knowing that although he could deny her nothing the thought of a bargain made him happy : “Look Ralph, I found this lovely dress on sale for £2.50 in Harrods!” or “Such a lovely cardigan, and it cost a mere £3! I found it in Kensington where they have the most wonderful charity shops!”. She negotiated with him endlessly over whether he might keep any of the second hand “treasures” he brought home from skips and rubbish piles.

And yet he never hesitated to put his hand in his pocket for others when he felt it necessary. He paid for the private education of several children, insisting on anonymity. Once when he was waiting at a taxi rank late at night, the Controller called all the drivers to applaud him as the most generous man they would ever meet: Ralph had lent the man £8,000 to cover an unexpected rent rise at his shoe shop in the days when a working class man had no hope of a bank loan for such a sum. The mainly Iraqi drivers looked mystified but gave Ralph their vigorous applause.

Betty introduced Ralph to auctions in the hope that it might distract him from skips and, as usual, she was correct. As his love for fine antique jewellery, then furniture and eventually paintings developed, he started to visit auctions regularly and slowly learned to buy for himself. He found the bidding exciting and it satisfied his desire for a bargain.

There was an ebb and flow with his acquisitions. He could never bring himself to sell anything he bought but over the years, burglars depleted his collection. He never bought an insurance policy (following the maxim that there is no need to insure anything which is either irreplaceable or which you can afford to replace) but the losses to him were personal, not financial, because he loved each purchase. In his retirement, he attended a viewing of an upcoming sale at least once a week. Although he loathed parties, his mantel was often crowded with invitations to viewings from the biggest auction houses and he dined regularly (although standing up) on free champagne and oysters in the sale rooms.

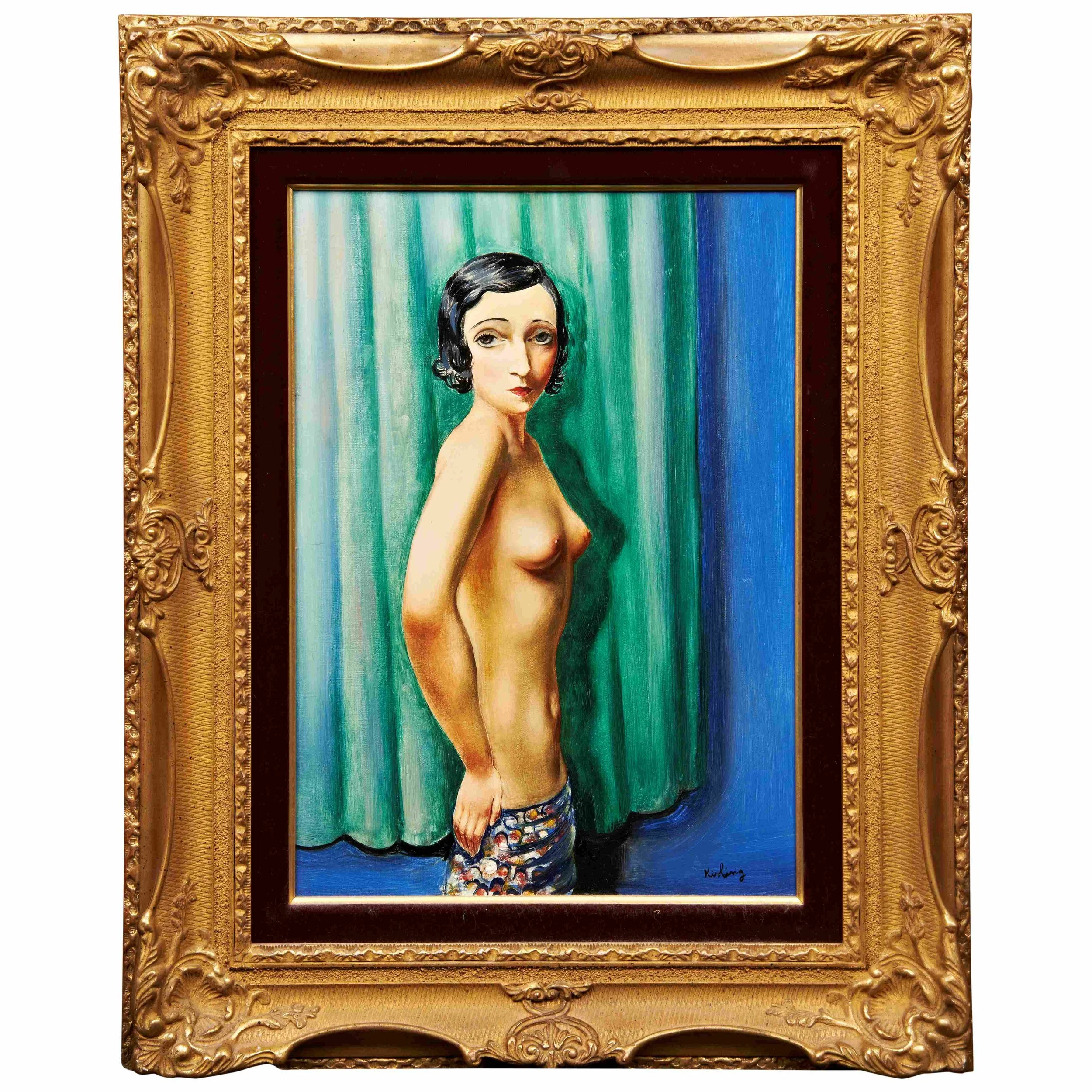

In the mid-nineties, he encountered the work of the painter Moise Kisling and was smitten. Ralph never cared whether an artist was well known but, to his mind, Kisling’s models resembled his wife Betty and he started to buy any Kisling which came up for sale and which he could afford. Betty didn’t share his enthusiasm and denied the likeness but the models are mostly petite with short dark hair. In the hope of endearing Betty to Kisling’s work, he bought her two paintings of flowers because she loved gardening but it was a lost cause. Eventually he gave most of the Kislings to his children, consoling himself with the knowledge that at least they would escape inheritance tax. Like many successful men, paying tax gave him no pleasure although his accountant, who was one of his few friends, insisted on it. The Tax Office probably found Ralph as full of contrasts and eccentricities as the rest of us as Ralph’s proudest anecdote concerned a tax inspector who, at the end of a lengthy negotiation concerning the dentist/property developer/plumber, said to Ralph’s accountant: “Off the record, please tell me: does Mr Bateman really exist?”.

Request auction estimate

We offer free auction estimates by email or by appointment. We will review your items and provide you with an indication of the guide value at which Dore & Rees believe the item would be offered for sale.

Please send us an email with good quality photographs, dimensions, history, provenance and known background. Alternatively, do give us a call to discuss your item.